Stray Dog Ruling: A Relief, Not a Resolution

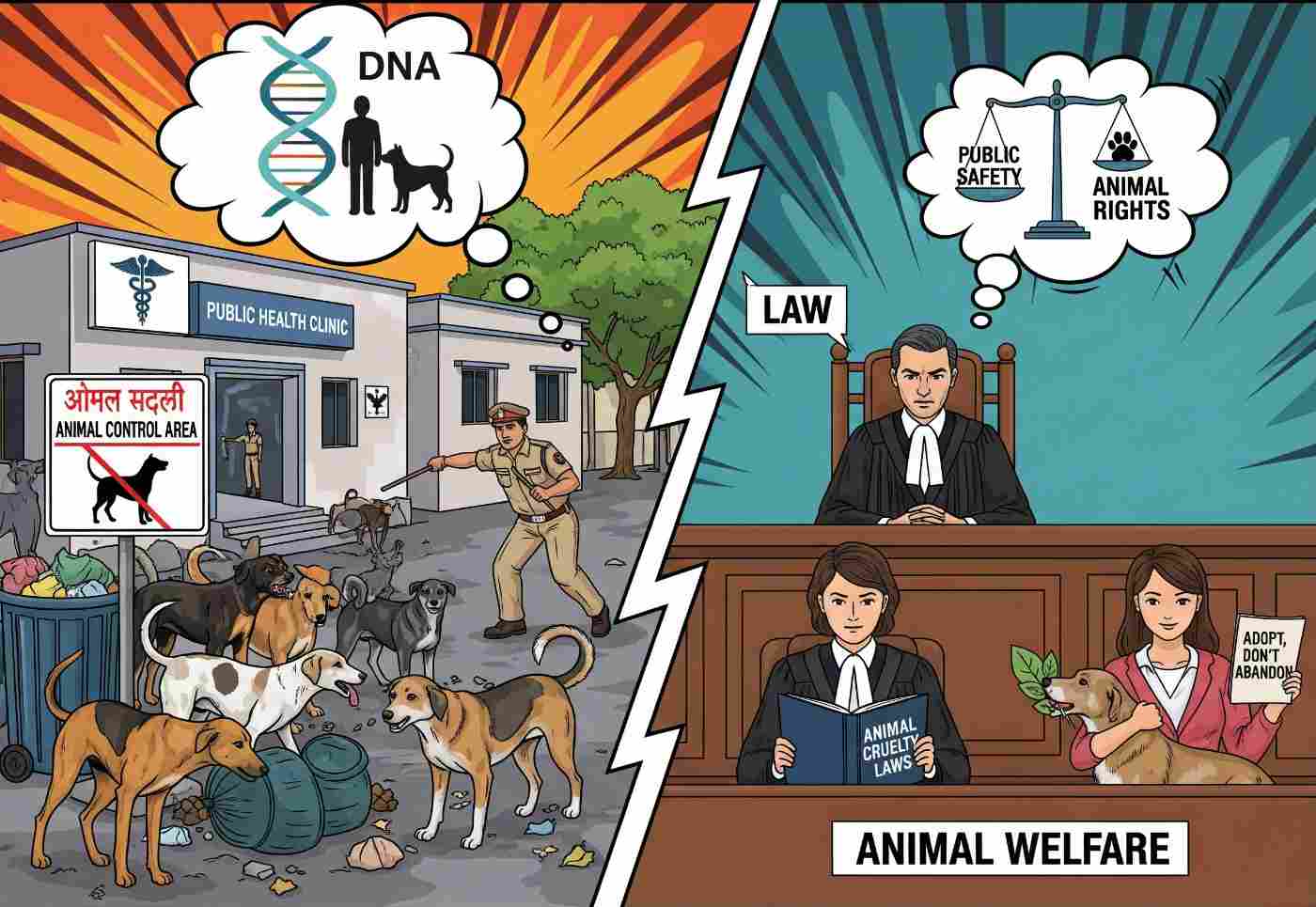

The Supreme Court’s decision on stray dogs, delivered on Friday, offers relief to animal welfare groups but leaves several hard questions unanswered. By modifying its earlier order that all dogs in Delhi-NCR be permanently confined to shelters, the Court has restored the principle of sterilisation, vaccination, and release—a method backed by both science and international practice. Yet, the ruling is far from a comprehensive response to the crisis of rising dog-bite incidents and rabies deaths across India.

The August 11 directive to confine all strays had drawn widespread criticism as impractical and inhumane. India lacks the infrastructure to house lakhs of dogs, and overcrowded shelters would only worsen animal suffering. The Court’s course correction is welcome. But the prohibition on street feeding, unless at designated zones, risks deepening conflict between civic authorities and animal feeders. As several veterinarians have noted, starving dogs are more aggressive, not less.

The case’s expansion into a pan-India exercise underscores the scale of the challenge. India has over 1.5 crore stray dogs, and civic bodies across States are struggling with limited budgets, poor sterilisation rates, and weak enforcement. A uniform judicial diktat may not be the answer. States such as Kerala, which has witnessed violent public backlash against strays, cannot be equated with Bengaluru, where citizen groups collaborate with authorities on sterilisation. Local contexts demand local solutions.

The Court’s decision to require petitioners to deposit large sums of money is equally troubling. While intended to ensure accountability, it risks silencing smaller welfare groups that have long filled the vacuum left by municipal indifference. Civic bodies, not NGOs or individual feeders, must be held primarily responsible.

Ultimately, sterilisation-and-release can work only if implemented at scale, backed by scientific monitoring, and coupled with mass anti-rabies vaccination. This requires political will, budgetary allocation, and community participation—none of which a court order alone can mandate. The present ruling is thus a halfway house: it averts the cruelty of mass confinement, but leaves unresolved the deeper governance failures that perpetuate the stray dog-human conflict.

India must move beyond litigation-driven firefighting and treat this as a public health challenge. Until then, the cycle of judicial orders, activist petitions, and civic inaction will repeat itself—at the cost of both human safety and animal welfare.